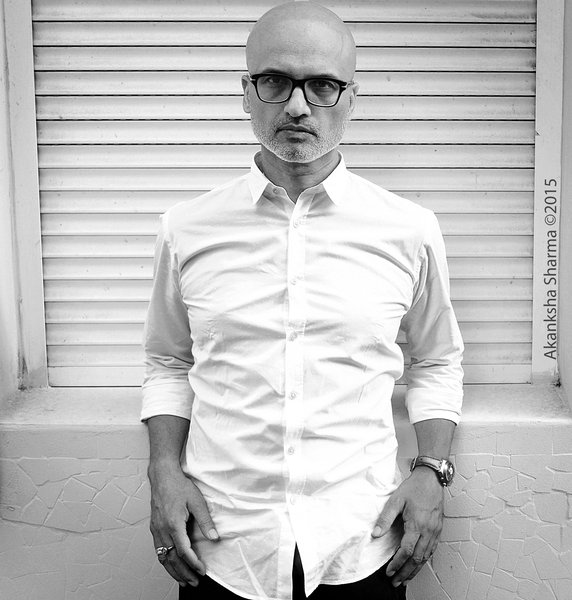

Guy Somerset • 2 March 2018

As he heads to Writers & Readers, Man Booker Prize-shortlisted Jeet Thayil talks about his country’s violence against women, VS Naipaul as God and quoting Fleetwood Mac in his new novel The Book of Chocolate Saints.

Jeet appears at 2018 Writers & Readers in Jeet Thayil: Post-Narcopolis, in conversation with Gregory O’Brien, 2.45–3.45pm, Saturday 10 March, Renouf Foyer, Michael Fowler Centre.

There is a line near the beginning of Indian writer Jeet Thayil’s Man Booker Prize-shortlisted 2012 debut novel, Narcopolis, that describes the allure of opium – “such a sweet meditation, no, more than meditation, it’s the bliss that allows calm to settle on the spirit and renders velocity manageable, yes, lovely”.

Readers of Thayil’s fictional account of Bombay’s drugs demi-monde in the 1970s–1990s, informed by his own, now-passed years of addiction (the novel is dedicated to “H.C.V.” – the hepatitis C virus he contracted), would not be many pages through the book before they started to recognise that same bliss in Thayil’s writing, as it manages the velocity of the city he depicts, replete with junkies, prostitutes, corruption and crime, including a serial murderer called “the stone killer”.

If Narcopolis is one of the great city novels, Thayil’s follow-up, The Book of Chocolate Saints, pulls the lens outward in order to capture an even bigger view of India – its history, its literature, its religions, its caste system; its men’s predatory behaviour toward women; its place in the world and the place of its people when they go out into that world (England and France in the 1950s and 60s, post-9/11 America).

-"If Narcopolis is one of the great city novels, Thayil’s follow-up, The Book of Chocolate Saints, pulls the lens outward in order to capture an even bigger view of India"

The character who provides the focus for all this is one Narcopolis readers will remember from his brief but eventful cameo in that novel: poet and painter Newton Francis Xavier, a man whose alcoholic and sexual appetites are as enormous as his talent. And frequently as misspent.

In The Book of Chocolate Saints (the title comes from the series of poems Xavier is writing highlighting the many saints eclipsed in Christianity, “a directory in which there would be no pale faces, only dark and darker, as a counterbalance against the many books in the world that had no black or brown or yellow faces”), we accompany Xavier through his life from childhood.

Xavier makes such an impression in his few pages in Narcopolis you can see why Thayil would want to bring him back, but in fact the character always had a more prominent role.

Both Narcopolis and The Book of Chocolate Saints are “carved out” of a larger, 1000-page novel Thayil had been working on, he says, speaking from his home in Bangalore before heading to Wellington for the 2018 New Zealand Festival Writers & Readers.

Once he finished Narcopolis, he returned to his original manuscript, and Xavier’s role in it grew, becoming the pivot on which everything else turns after his editor pointed out to him, “This is Xavier’s life.”

“Of course,” says Thayil. “I should have known that. But when you’ve been immersed in something for six years you forget the focus of it sometimes. As soon as he said this to me, which seemed like such an obvious comment, it just opened various doors for me. And then I went back to the book with a whole new engine. A narrower engine in a way. And that led to this 100-page oral history section we then split into three parts. And that made the structure also fall into place with a very satisfying series of clicks.”

The Book of Chocolate Saints is highly educative about Indian literary history, but also highly misleading, because “it was one of my aims to blur the line between fact and fiction” – with genuine poets, movements and literary events appearing alongside fabricated ones. (Thayil himself is one of the real-life figures, unnamed but recognisable in a character’s description of “a poet whose name I can never remember, skeletal fellow, strung out or drunk, who put together an anthology some years later, The Bloodshot Book of Contemporary Indian Poets, or something like that”. That would be The Bloodaxe Book of Contemporary Indian Poets, published by Thayil in 2008.)

Indian literary history – real or imagined, as a counterpart to literary histories in which it is eclipsed – is, however, “nothing more than a peg on which to hang the portrait of a society. And it’s the portrait of a society in the midst of tremendous social change. When you come to the more contemporary parts of the book you see how those things have flourished in today’s India”.

And how, I wonder, has today’s India received the novel? Is India a self-reflective society that takes a perspective such as Thayil’s well?

“Excuse me for laughing,” he says, “but I like that question so much. I think it just brightens my day.

"I’m laughing because if I had to describe in one word the manner in which this book has been received in India I would use the word incomprehension. Tempered with a generalised rage.”

-"I’m laughing because if I had to describe in one word the manner in which this book has been received in India I would use the word incomprehension"

Thayil is particularly perplexed by accusations of misogyny Indian reviewers have levelled against the novel, with initial reviews setting a pattern later ones have followed, he says.

You can appreciate his bafflement: the novel certainly depicts misogyny, but clearly to critique not endorse it.

“If you remember the horrific Delhi rape, it’s been several years since that happened and nothing has changed,” says Thayil. “You read daily reports in Indian newspapers about horrifying violent rapes. Violence against women that never seems to end. There’s a character in the book whose massive source of anguish is violence against women. In fact there are entire passages where she talks about how disgusting Indian men are. And this for me is one of the crucial parts of this novel.

“It was something I was hoping would be spoken about. Would be discussed. Would be talked about in India. But so far it has not happened. And it shouldn’t surprise and appal me that the first time I’m having this conversation is with an observer from a foreign country. But it does. It appals me.”

A powerful section of The Book of Chocolate Saints is set in New York on and in the aftermath of September 11, 2001.

Like the journalist in the novel, at the time Thayil was working for what in the book is called Indian Angle, “New York’s Indian newspaper of record”, published and edited by the ferocious Mrs Merchant.

“I was in New York on 9/11,” says Thayil. “I was going to work at my newspaper office when it happened. I was in a subway. All of us had to come out of the subway. I ended up having to walk to work. I filed a story at 12pm. One of the first things that happened was a story about a Sikh financial market worker who was chased by two construction guys as the towers came down because they mistook his Sikh turban for an al-Qaeda turban.

-"I was in New York on 9/11. I was going to work at my newspaper office when it happened"

“I followed that story and I followed the story of Balbir Singh Sodhi who was assassinated in Arizona around the same time by someone who again mistook his Sikh turban for another kind of turban.

“Those parts of the novel, of course they’re imaginatively rendered, but they are absolutely based on true occurrences. To the extent that even some of the names have only been changed minimally.”

Post-9/11, Thayil writes in the novel, was very much “Post America” and all the country was meant to represent. It has, of course, only got worse since the election of President Donald Trump, I say.

“All those things were in the works in the 2000s, especially after 9/11, but with Trump it has been ramped up to an extent I don’t think America could ever have envisioned. Today America is a society that has been divided very clearly along racial and cultural lines – divided in such a way there are people of both races on both sides of those lines, which makes for a kind of schizophrenic society.

“I think it’s a terrible time for America, especially if you’ve had any feeling for what America – the word America, the idea of America – stands for. It’s heartbreaking to see what’s happening there now. I have family and friends there, in fact close family and friends, but I don’t travel there.”

-"I think it’s a terrible time for America, especially if you’ve had any feeling for what America – the word America, the idea of America – stands for"

Of the many walk-on parts by real-life figures in The Book of Chocolate Saints – from TS Eliot to Allen Ginsberg – the most audacious is Thayil’s portrayal of notoriously ornery Indian-Trinidadian writer VS Naipaul as God. Albeit in a dream sequence featuring Xavier’s mother in a lunatic asylum.

It’s an inspired piece of casting and understandably one of Thayil’s favourite parts of the novel. “I’m still surprised, and very happily surprised, that it found its way into print. I expected someone to say, ‘No, wait, we can’t do this.’”

-“I’m still surprised, and very happily surprised, that it found its way into print. I expected someone to say, ‘No, wait, we can’t do this”

Both a poet and a novelist – and indeed a librettist and a musician – Thayil has a character in The Book of Chocolate Saints make the comparison “as conservative as bankers or novelists”.

“Well, I’m always more admiring of poets than of novelists,” he says. “Because as a friend of mine recently pointed out, and she’s a poet, poetry is the only thing that is written not for money. There’s no question that poetry is not written for money. Because nobody in his right mind would expect to make a fortune out of poetry. That’s just not the criteria in ever wanting to write a poem.

“And what that means is immediately you know that when you read a poem you are reading a purer endeavour than any other kind of writing. Novels have a hundred different things going on there. A novelist is a completely different kind of creature to a poet. And you really have to pity those writers who pursue both forms.”

So what tempted Thayil?

“I quit my paying job in 2004 and focused purely on writing. And I wrote poetry – did a couple of books of poems, edited an anthology of poetry. But if all you’re doing all day is writing, how can you not spread your wings? How can you not be a writer rather than, say, a poet or a novelist or a librettist alone and do nothing else? I would just bore myself to tears in a couple of years.”

Of course, nobody in their right mind would expect to make a fortune out of writing novels either – although being shortlisted for the Man Booker Prize would probably make a difference.

“When you are writing a literary novel, in some ways it is similar to writing poetry. You don’t expect overnight riches or celebrity or any of those things. I thought I had written a novel that could only be described as a literary novel. And I thought that in time, in five or seven or eight years, it would find its audience and would slowly assume a reputation.

“But because it was shortlisted for the Booker Prize it did change everything. It got so much attention almost immediately. And of course the minute that happened what I started to worry about is what am I going to do now for the second novel? Because when you write a first novel there’s really no pressure at all. Nobody knows you. Nobody expects anything from you. You don’t expect much yourself. So you can’t let yourself down. You can’t let anybody down. But once you’ve published and it has got some kind of attention, there is pressure. And I really think the second novel might be the most difficult thing for a writer to pull off.”

-"Because it was shortlisted for the Booker Prize it did change everything. It got so much attention almost immediately"

Which begs the question about the third novel.

“Well, I’ve already started work on that. It’s a collection of stories and essays that are juxtaposed in such a way that you don’t know which is the fiction and which is the nonfiction. Except for the prologue which is very clearly nonfiction. It’s a story about meeting Naipaul over the course of several years.”

Naipaul again. What’s Naipaul ever done to him?

“He hasn’t done anything to me,” laughs Thayil. “But I really do think of him as the man in my head, to use Pico Iyer’s phrase. Because it’s not just his bleak intellectual vision of the world, the colonial world and the postcolonial world; it’s also the fact that, although he denies this, there is an element of poetry to the way he approaches the English sentence. He would go out of his way to deny anything poetic there but there’s a reason poets have loved Naipaul for decades. Poets whenever they come across that prose they respond to it instinctively. The prose has a kind of clarity and a kind of ease and a simplicity that poetry often aspires to.

“That kind of regard, it has something to do with how one looks at one’s literary parents, forebears. That kind of regard is equal parts love and hate.”

On the subject of love, is that really a Fleetwood Mac quote I saw in the novel?

“Of course it is. Of course it is. I’ve always loved those words: ‘Players only love you when they’re playing/Say women they will come and they will go/When the rain washes you clean, you'll know.’ Excellent.”

Excellent indeed. There’s also a David Bowie quote in there somewhere, says Thayil.

A novel of many, many riches.

Guy Somerset was the founding editor of ARTicle Magazine. He is a former Books & Culture Editor of NZ Listener and Books Editor of The Dominion Post.